“Lisbon welcomed us with light, music, and laughter.” Wrote Alfred Döblin when arriving in Lisbon in the summer of 1940 while the world was at war.

Alfred Döblin, the Author of Berlim Alexanderplatz (1929) arrived in Lisbon among several others refugees escaping the war and persecution. This was the summer of 1940, the Blitzkrieg looked unstoppable, the Germans conquered Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg and occupied France. In desperation, many looked at Portugal. The country was neutral during the world conflict and Lisbon, with an international port, provided an exit for all those who could no longer stay.

The author knew almost nothing of Lisbon besides being the capital of Portugal and that it was here that a terrible earthquake happened which inspired Voltaire to make “his biting comments on optimism and ours being the best of all possible worlds”. A cultural visit to Lisbon was not the purpose, Lisbon was only the departure station.

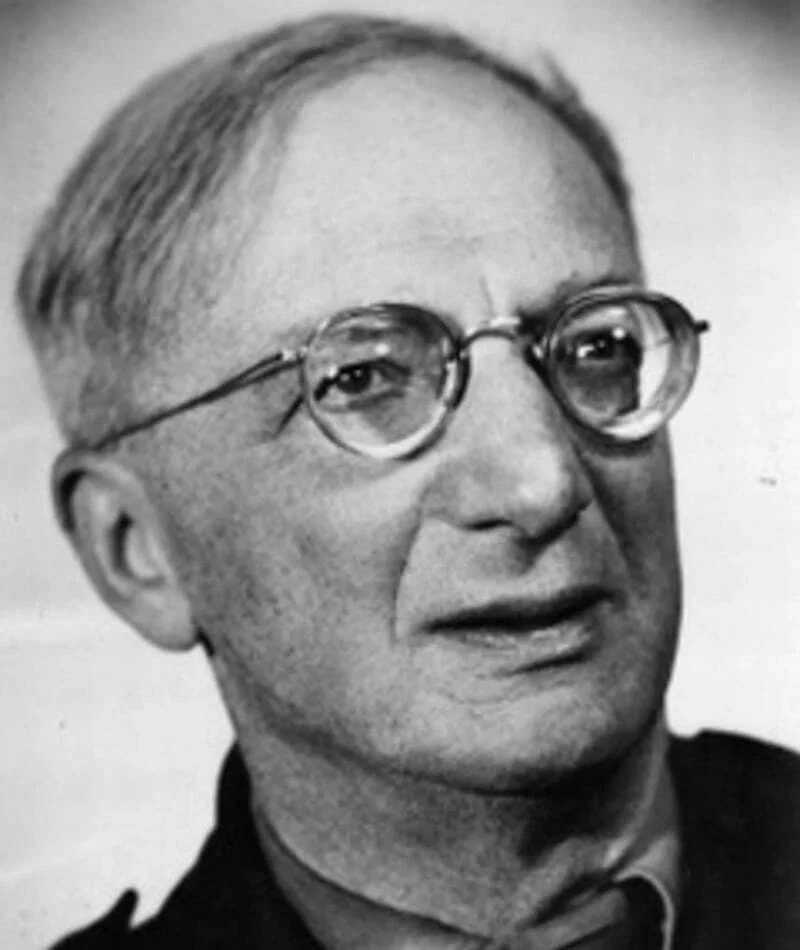

Who was Alfred Döblin?

Alfred Döblin was Born in 1878 in Stettin (today Poland) to a family of cultural Jews. He lived several years in Berlin and besides being a medical doctor, he wrote novels, drams, radio plays, screenplays, and philosophical, political, and medical essays. He belonged to the same generation as Thomas Mann, Franz Kafka, Robert Musil, and Erich Maria Remarque. Being almost unknown to the Portuguese audience he is recognized as one of the major German writers of the 20th century. His masterpiece, Berlin Alexanderplatz was an immediate success when it was published and regained a new audience with the TV adaptation from Rainer Werner Fassbinder in 1979. Berlin Alexanderplatz is frequently compared to James Joyce’s Ulisses and Manhattan Transfer by John Dos Passos.

His studies in Medicine and his career in the area of Psychiatry and neurology — at a time when many profound conceptual changes regarding the human brain and psychology were happening — strongly influenced his writing. According to his admission, his job as a clinician was a part of his writing and political thought.

Döblin’s connection to Judaism was more cultural than religious, but as a Jew in Germany, he suffered anti-semitism early in his life. With the ascent of Adolf Hitler in 1933, Alfred Döblin and his family left Berlin to settle in Paris. With the German occupation of Paris, the author is forced once again to leave and this time, to leave Europe altogether.

Döblin in Portugal

The time Döblin spent in Portugal is described in his book Destiny’s journey first published in 1949. The book is divided into 3 parts, each one accounting for the years in exile, the first in France, the escape out of Europe, and the time spent in the United States. Chapter 14 is dedicated to Portugal and Lisbon.

The Döblin family enters Portugal with anxiety. Several rumors were circulating about the way the refugees were received in Portugal. The country had received in that year alone about 38 000 foreign people, the majority of refugees forced to wait months until they receive a ticket to leave Europe.

The rumors we had heard about Portugal were less than pleasant: we would be held at the train station on arrival, we would not be allowed to into Lisbon, in Lisbon there were already thousands of refugees waiting, the police shunted new arrivals into camps in the provinces. Steeped in these rumors, we now set out courageously from the train. We joined the throng crowding the gate. We handed over our tickets like ordinary passengers. No passports were required of us. No one detained us. Lisbon accepted us as naturally as it later disappointed us.

Döblin Destiny’s Journey. p. 214

“Lisbon welcomed us with light, music, and laughter.”

The chapter goes on to describe the first impressions Lisbon left on the Döblin family. Arriving from other countries in Europe, in darkness due to the war, Lisbon, as a neutral city was filled with neon light. The contrast between the happiness around them and the misery they felt can be felt in his words.

Lisbon welcomed us with light, music, and laughter.

We will never forget the jolt it gave us. Nor far from here, France was in agony, its city engulfed in the shadows of war, the northern part of the country overrun by its conquerors. People were suffering and hungry, were waiting to see what conditions the victors would dictate. Millions of men had been taken prisoner, millions lived in terror, tens of thousands had been killed —and here the lights were burning brightly. People were enjoying peacetime.

We couldn’t enjoy it. We could think only of what we had left behind.

Döblin Destiny’s Journey. p. 214

The family stayed at a residential hotel in downtown Lisbon, in Rua dos Fanqueiros. The hotel no longer exists and the lively descriptions of Döblin of the surrounding area have been transformed in the last decades. In the 1940s Fanqueiros Street was a street filled with several clothing shops. The Praça da Figueira nearby had one of the busiest markets in the capital. All this commercial activity has been replaced with restaurants, hotels, cafés, and souvenir shops.

What impresses Döblin are the loud sounds of the city.

We were living in the loudest traffic center in the city. A furrier occupied the other half of the third floor we were staying on, there were dining rooms downstairs and a doctor’s consultation rooms. At the foot of the stairs was the parterre, and a clothing and lingerie merchant had spread out his wares in the wide hallway. We had to wend our way past his display table and his customers to get to the street. (…)

Most of the shops offered clothing and lingerie fabric for sale. Merchants not only filled their shops and display windows with the rolls of fabric, they wheeled them out in front of their shops and draped them over the doors. They offered their wares for sale each morning, and each evening they rolled it all up and put it away. The entire area shrunk of Saturdays. And on Sundays it was only the gray private houses that faced each other on the now totally silent street, their eyes cast down as if they had Benn caught in a transgression. But even then they were secretly thinking about their raucous wickedness, of course, and were waiting only for Monday morning to arrive so that they could resume their old activity once again.

Döblin Destiny’s Journey. p.216

And no other sound impressed Alfred Döblin more than the tram cars. Although trams are part of normal public transit in Lisbon, they are fewer nowadays and are generally considered charming and a tourist attraction.

If there is one fundamental thing I should mention about Lisbon, other than the monstrous heat and the sweltering air, it is the noise. (…) Lisbon is a modern, large-scale factory for the production of noise. First there are the electric trams. They run close together, with or without passengers. They jolt along on. The rails, they clatter along the tracks, they cause the glass in the windows to rattle. The conductor has at least one bell at his disposal, and probably two. A Portuguese conductor can make them sound like three bells when he rings them — and he rings them incessantly, he gets great enjoyment form it. He conducts bells.

Döblin Destiny’s Journey. p. 225

At the front of the gram is a sturdy safety device shaped like a shovel. When the can turns a corner, you net the impressionante that the thing wants to how down pedestrians. The tram cars in Lisbon like to turn corners, they actually prefer corners, and it is for this reason that Lisbon is equipped with so many corners, because turning corners makes possible a rich variety of sounds.

Döblin Destiny’s Journey. p. 225

The cars, however, are not far behind.

(…)We all recognize the make of cars, but in the city of Lisbon cars manifest their characters in ways unknown elsewhere. For one thing, they move in an indescribably intricate fashion. The ideia of starting up, the mere plan, the intention to move puts these cars, which apparently doze off very quickly, in a dangerous state of excitement, so that they begin to hiss like snakes. This is the way they express their intention to get going. Then they purr and growl. I avoided cars in Lisbon, for I didn’t understand their language and who knew what they were capable of? (…) some cars, if left to their own devices while under way, begin to snore contentedly. Some start honking with no warning. Some of them snort like a rhinoceros with a stuffy nose. At night, we often heard cars in the distance that were fighting with one another. They must have been married.

Döblin Destiny’s Journey. p. 226

Throughout the chapter, we are confronted with the difficulties the family faces, from lack of money, the anxiety when faced with the Portuguese bureaucracy, the unbearable Summer heat, and the long wait. Most of the refugees that came to Lisbon during this time were in transit to other destinations out of Europe, mostly to the United States. They had a temporary permit to stay and they need a visa and a ticket to a transcontinental ship, this meant waiting for weeks and even months. They were not allowed to work and the majority were able to survive with the help of several Jewish organizations, both Portuguese and international.

To spend time, like the Döblin family, they sat in cafés, placed chairs outside to enjoy the sun, and wandered through the city. The observations of Alfred Döblin of the city life and inhabitants make obvious the cultural differences between Portugal and the rest of Europe.

There appeared occasionally from a side street a group that looked as if they had stepped out of the Bible. These robust, straight-backed women marched into the city in a single line, one behind the other, carrying jugs and baskets on their heads. The baskets were filled with fish or fruit. There was a large market hall on the side street with an abundance of fruit, vegetables, meat, and fish — an unbelievable sight.

Döblin Destiny’s Journey. p. 216/7

(…) It’s a splendid city with a large number of interesting monuments, exquisite shops, and a brisk commercial life. The city is built on hills at the broad mouth of the Tagus. The harbor is deep enough to accommodate large ships. As the city is close both to the sea and to a major river, an amazing amount of fish is sold and eaten here. We often went walking in the area around the harbor. There were always hundreds of men and women waiting there with their baskets for the fishing boats to arrive. They transported the fish into the city and to the market halls. It was an incredible sight each time to see the women balancing the flat baskets on their heads, their heads held high as they walked along with a steady, elastic gait, their bodies bent slightly forward.

Döblin Destiny’s Journey. p. 224

Street youths jump onto the car while it’s in motion, they’re barefoot, wearing torn jackets and pants, they’re newsboys. On the hill you can see the original monument to such a boy. They deserve a monument — perhaps one day someone will also buy them jackets and pants. The boys shout as they leap onto the car. It’s in their nature, and it’s also part of their profession. They shout the news. Once I saw a boy running after a tram car with a cigarette in his hand, he had seen a man in the car who was smoking. With one leap the boy was hanging on to the outside of the car, the man lit his cigarette, the boy thanked him, shouted, jumped off, and kept shouting.

Döblin Destiny’s Journey. p. 226

Besides the Cafés, hotels, and markets, one of the most sought places in Lisbon was the Posta Restante, the international Post Office where the refugees looked out for family news or other important mail.

Legions of them were standing in lines there, refugees, the shipwrecked, inquiring after letters and telegrams. Most of them were well-dressed men and women who wore the signs of their fate on their faces and in their gestures: the sad disquiet and anxiety. This poste restante corner in Lisbon, in Portugal, in this outermost corner of Europe, was the tragic meeting place for many in the unhappy year of 1940, a year that had exposed the frivolity and thoughtlessness of the false calm of the past. Entire nations were being enslaved, families scattered. Europe was doing penance for its sins and omissions. And we refugees, subjects of this Europe, were standing here in Lisbon and waiting for the life buoy to be tossed to us from the other side of the ocean.

Döblin Destiny’s Journey. p. 218

Alfred Döblin and his family left Portugal in October 1940 for the United States of America. From the ship, he sees once again the lights of the city and the Exhibition of the Portuguese World commissioned by the Government of Salazar.

We went to the harbor — and then it was over an hour before we could board the ship. Dozens of people stood waiting on the dock. And when the signal to board finally was given there was so much crowding that a clerk called down to appease us: “No pushing, ladies and gentlemen, no crowding. The Nazis aren’t after you here.” The centennial exhibition across the water glittered as in a fairy tale. It’s magical light was the last we saw of a Europe sunk in sorrow.

Döblin Destiny’s Journey. p. 235

In the United States, Döblin converted to Catholicism but he didn’t stay long. He returned to Germany in 1945, but disappointed with the Post-war situation in the country, he leaves again for France. Alfred Döblin died in 1957.

The experience of Alfred Döblin and other refugees in Lisbon during World War II is covered in the guided tour Lisbon between Refugees and spies.

Referências:

Citations are taken from Alfred Döblin, Destiny’s Journey. Ney York. Paragon House. 1992

A Companion to the works of Alfred Döblin ed. Roland Dollinger, Wulf Koepke, Heidi Thomann Tewarson

This article was also published in Portuguese on Historialx.com